Games as storytelling partners

What, exactly, is a game? And isn’t that kind of an impossibly loaded question? (It is, but I’m going to try to answer it anyway!) In this post, I’ll be making the argument that it can be useful to view games in general as storytelling partners for their players.

First, let’s go over a few (possibly debatable) assumptions I’ll be making about narrative in games:

The narrative happens in the player’s head. It is the story the player tells themselves about their experience – the story they construct to make sense of the events unfolding before them.

Even “non-narrative” games have a narrative dimension. Consider, for example, such a clearly abstract game as Tetris. Despite the total absence of concrete characters, setting, and plot, the experience of playing is still linearized as a narrative in the player’s head.1 As the game progresses, a skilled player may find themselves living out a story of rising tension, spectacular last-second saves, and even an escalating antagonistic relationship with the RNG as it repeatedly refuses them the piece they need to survive.

The player is necessarily a co-author of the narrative. No matter how careful you are as a designer, the player will inevitably miss some story-relevant details, misinterpret others, and bring their own unique perspective to the process of interpretation – and that’s before we even get into the issue of player choice! Thus, you cannot make any guarantees about the story the player will actually experience. You can only set up a possibility space that naturally affords certain kinds of narrative experiences for the player to explore.

The narrative is built on buts and therefores. “I wanted A, so I did B in order to get it. But C got in the way, so I was forced to do D instead…”

Taken together, these four assumptions lead more or less directly to a fifth key point, which is the actual subject of this post:

To play a game is to co-create a narrative with the game. The player and game, in other words, are creative partners. They take turns reacting to one another’s actions, creating in the process a sequence of interconnected “buts” and “therefores” that collectively comprise a narrative.2

What does this perspective give us? Among other things, it gives us a way to evaluate games based on the kinds of storytelling assistance they provide! For instance, I find that a lot of my favorite games are like good improv partners in their willingness to say “yes, and…” when I try taking the story in a particular direction.

@eevee the best surprises in games go like this:

— Max Kreminski (@maxkreminski) April 20, 2016

1. wonder if it'll let me do that

2. nah, no way

3. [does it anyway]

4. holy shit it worked

When I try something a little silly or off-the-wall, the game doesn’t shut me down or tell me I can’t do that. Instead, it recognizes what I was attempting to do and builds on it, reacting in almost exactly the way I was hoping it would – but with an interesting twist of its own that gives me something else to react to.

(Can I catch that dragon with my fishing rod if I use something shiny as bait and line up the throw just right? Haha, there’s no way that would work. Guess it’s worth a shot, thOH F*** WHAT DO I DO NOW)

This builds up a neat little feedback loop of action-and-reaction. The game and I are now batting the storytelling initiative back and forth like a tennis ball, and an interesting narrative has begun to emerge.

"What happens if I do this?"

— Dan Hindes (@dhindes) March 11, 2017

- Good games have an answer

- Great games have an unexpected answer

- Interesting games raise another question

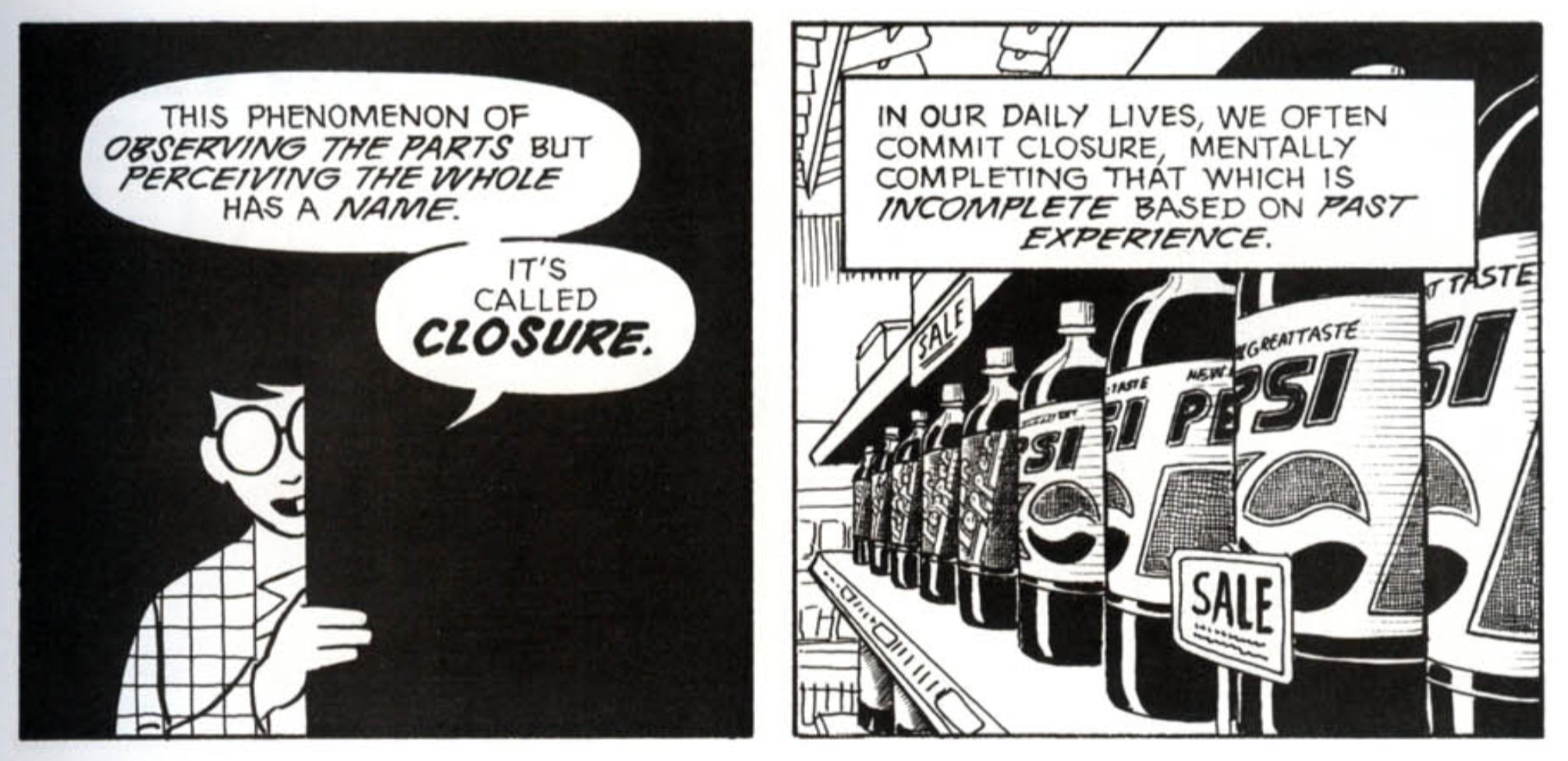

Another way of looking at this feedback loop is through the lens of closure, as discussed by Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics:

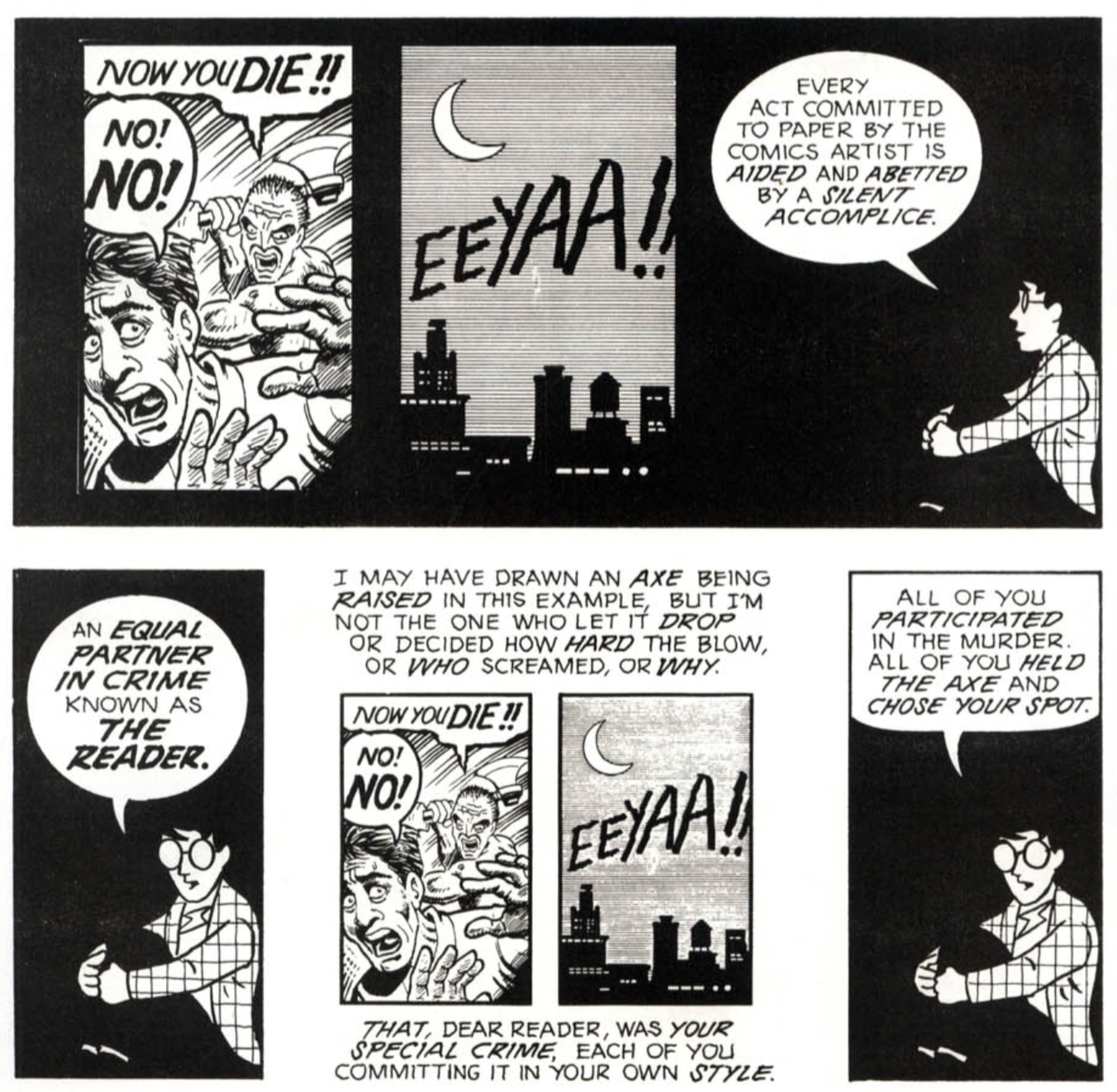

McCloud uses the term “closure” to refer to the thing that happens in the reader’s mind when they fill in missing details in a story – like, say, what exactly happened in the “gutter” between two consecutive comic panels. Closure is an essential part of storytelling in comics; you could even argue that a comic alone contains only the skeleton of a narrative, and that the narrative is not realized or instantiated until a reader comes along and does closure to it.

In this sense, the narrative of a comic is in fact constructed partly by the reader, who serves as the author’s “silent accomplice” – a storytelling “partner in crime”. Without a closure-committing reader to fill in the gaps, keep a lookout, and drive the getaway vehicle, the story is fundamentally incomplete.

One key difference between games and comics is that games are capable of committing closure back: of “reading” the player’s concrete actions and filling in the gaps between them to interpret the player’s intent. Comics, as a rule, don’t attempt to read the reader and adjust themselves in response; games, as a rule, absolutely do. And because games can and do read the player, they end up behaving more like storytelling partners: capable, to some extent, of “going with the flow”, letting the player guide the story in new directions on the fly.

Perhaps the weirdest consequence of this perspective is that, if you take it really seriously, it starts making sense to think and talk about games as agents – decision-making entities with goals and desires of their own. As an agent, a game can’t really be said to contain a single fixed narrative; it can, however, be said to have certain kinds of narratives that it wants to tell.

This also helps explain the appeal of Let’s Plays, gameplay streams, and gameplay-driven video series like Car Boys. The popularity of these things might at first seem paradoxical: they’re all about watching other people play games, when the fun of games is “supposed to” lie in playing them yourself. But when you change your perspective a little, all of these can essentially be seen as instances of improvisational storytelling in which one of the storytellers just happens to be a game.

I, for one, find this perspective shift immensely exciting. What can we learn by looking at, say, chess as an active storytelling partner for the players? What about Super Mario Bros.? Animal Crossing? Any of a wide variety of sports? I don’t know just yet, but I’m definitely looking forward to finding out.

Footnotes

[^1] Jack Post has also written about the narrative dimension of Tetris in particular, and comes to a similar conclusion:

An abstract and non-narrative game like Tetris has narrative structures, not because it has settings, events and characters, but because of its complex [Narrative Program] and tactic dimensions, and because the interactivity of its gameplay can be analyzed in narrative terms.

In essence, because the experience of interacting with a game can itself unfold as a narrative in the player’s head, a game doesn’t necessarily have to provide any of the things we traditionally think of as “parts of narrative” (plot, characters, setting, and so on) for a “narrative structure” to emerge.

[^2] The perspective I’m taking here is closely related to the “story machine” approach to interactive storytelling. Under this perspective, a game is essentially a machine for generating interesting stories:

From this point of view, a good game is like a story machine — generating sequences of events that are very interesting indeed. Think of the thousands of stories created by the game of baseball or the game of golf. The designers of these games never had these stories in mind when they designed the games, but the games produced them, nonetheless.

This is obviously only one of several distinct ways that it’s possible to approach interactive storytelling in games, but it’s a perspective that I find very powerful – especially since it gives us a way to understand narrative experiences in games with few or no “baked-in” narrative elements (such as, say, the majority of sports).